Wednesday, March 30, 2011

UNIVERSITY: Caucasus Studies in Malmö, Sweden (mah.se)

EINLADUNG: Internationalen Armin T. Wegner Tagen 2011 (armin-t-wegner.de)

wir laden Sie ganz herzlich zu den Internationalen Armin T. Wegner Tagen 2011 und unserer alljährlichen Mitgliederversammlung in Wuppertal ein.

Um die eigentliche Mitgliederversammlung haben wir wieder ein interessantes Programm zusammengestellt, dessen Höhepunkt das Passionskonzert am 2. April um 18.00 Uhr in der Immanuelskirche in Wuppertal-Oberbarmen mit dem Oratorium für den ermordeten Journalisten Hrant Dink sein wird.

Ich möchte noch darauf hinweisen, dass nach zwei Jahren wieder der Vorstand der Armin T. Wegner Gesellschaft neu gewählt wird und Sie deshalb bitten, Nominierungen für den Vorstand einzureichen sowie zahlreich zur Mitgliederversammlung zu kommen, um sich an dieser Wahl zu beteiligen.

Berlin, den 10. Februar 2011

Thomas Flügge

Vorsitzender der Armin T. Wegner Gesellschaft Internationale Armin T. Wegner Tage 2011 vom 2. – 3. April in Wuppertal

Weitere Informationen unter :

www.armin-t-wegner.de

www.armin-t-wegner.us

FEATURE: Misha’s freedom laboratory. By David Goodhart (prospectmagazine.co.uk)

On my last night in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, a Frenchman was murdered in my hotel. As it was the Caucasus I immediately assumed there was some murky political motive behind the stabbing. I was with a group of other journalists on a tour of the country sponsored by the Georgian government, and when we discovered the victim was involved in the modernisation of Tbilisi’s transport system, our suspicions only grew.

It turned out to be a private liaison gone horribly wrong—a “normal” western murder in a country striving to be an outpost of the west in a dark corner of the post-Soviet world. Georgia aspires to be not just an outpost, but a model. Though the country is home to only 4.2m people, President Mikheil “Misha” Saakashvili aims to use its “soft power” to make it a beacon of political and economic freedom—much like west Berlin during the cold war—and an alternative to the region’s historic Russian master.

Earlier that evening I had met one of the president’s closest advisers in a drinking den near my hotel. The place was full of bohemian young Georgians and westerners working for NGOs, and it did remind me of west Berlin in the 1980s—down to the pleasingly retro Bob Dylan and Beatles music.

After many days of hearing about Georgia’s successful experiment with freedom from smart thirtysomething government ministers, or the failings of Saakashvili’s centralised, “guided” democracy from dowdier and older opposition figures, I still had a question that I had no proper answer to. It was one that I had hesitated to ask the president when I had met him earlier that day (see interview p50). I put it to his adviser instead.

Why, when the Middle East is on fire and the west is distracted by its power slipping eastwards, should anyone care about Georgia? The adviser had a good answer. “A lot of people in the west think that the colour revolutions in Ukraine, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan have all failed or slipped back. But that is not true of Georgia—we remain absolutely part of the west.”

And why does that matter? “In eastern Europe there was still some memory of pre-Soviet freedoms. Out here there was none. We are surrounded by Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia in the Russian Federation, the Caucasian former Soviet republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan, and then the countries of central Asia. These are not places with a tradition of the rule of law or liberalism or the market economy. We have shown that these things can work in this unpromising region. As well as being an economic and energy hub, we are the place that the west can exert soft power in central Asia and even Iran.”

He paused, and chuckled. “And that, by the way, makes us an existential threat to a Putin-style Russian way of doing things. Little Georgia is more of a threat to Russia than vice versa.”

*****

Flying into Tbilisi’s modern airport and travelling, at night, into the charming, brightly-lit city centre, mostly unscarred by ugly Soviet-era architecture, it is possible to imagine you are in Scandinavia rather than the Caucasus, with Russian missiles 35 miles up the road and Grozny, the once blood-splattered capital of Chechnya, about as far away as Birmingham is from London.

In the cold light of day Tbilisi, in which a quarter of the country’s population live, is of course nothing like Scandinavia. The crumbling facades on most buildings, the overmanned desks in the ministry lobbies, the pinched faces in the crowd, the persistent beggars, remind you that even in its affluent heart Georgia cannot so easily sweep away 70 years of Soviet rule.

Before my arrival I remembered it as one of the more pleasant parts of the old Soviet Union, a place with a long history, Black Sea resorts, its own language and wine (though also the birthplace of Stalin and his feared secret police chief, Lavrentiy Beria). I was also dimly aware of a disastrous post-Soviet period during which it was wracked by conflict and economic collapse and then ruled by the ineffective Eduard Shevardnadze, Gorbachev’s foreign minister. (The writer Wendell Steavenson lived in Tbilisi in the mid-1990s, when there were only three or four hours of electricity a day, and wrote a fond memoir of that period, Stories I Stole.)

Then in 2003 came the Rose revolution—the first of those US backed “colour” revolutions in former Soviet republics—when a young, liberal grouping within the Shevardnadze government took to the streets and grabbed power. It was a nationalist and a democratic and free-market revolution: Saakashvili and his supporters were like liberal Bolsheviks dragging Georgia out of its post-Soviet torpor and into the capitalist sunlight. They packed off the older generation into retirement. Then they did things such as sacking all 14,000 of the country’s traffic policemen on a single day to break a culture of petty corruption, before moving on to battle the serious gangsters (Georgians are big players in Russia’s mafia underworld).

The economy roared ahead and the lights went back on. A flat tax was introduced and the taxation take increased from 11 per cent to 30 per cent of GDP. The state was withdrawn from most of economic life but strengthened in everyday existence; it became possible to trust officialdom. Georgia remains poorer than many of its neighbours: its per capita GDP of $4,500 is about the same as Sri Lanka. Yet for most people in the country and small towns this creation of effective government was an incomparable blessing, and one which provides Saakashvili’s United National Movement with a solid base of electoral support.

Not everything went to plan. In 2007 a varied opposition movement—some wanting to turn the clock back, others wanting faster change—staged protests in Tbilisi. These were violently broken up and an opposition television channel was closed. This damaged the president’s reputation—making people wonder if he was a Caucasus strongman after all, albeit one who had mastered liberal rhetoric. In the 2008 presidential election Saakashvili, who had won 96 per cent of the vote in 2004, returned to earth with a majority of only 53 per cent.

And then came the confrontation with Russia. The Russians had looked on with dismay after the Rose revolution, as Georgia marched out of its orbit with an aggressive pro-western swagger. In 2006 Moscow banned most of Georgia’s exports. Then, after a somewhat reckless Saakashvili went on the offensive, the Russians grabbed the chance to push the Georgians out of the two “autonomous regions” in the north of the country—Abkhazia and South Ossetia—in the five-day war of August 2008.

The fact that the Russian flag is raised just 35 miles from Tbilisi, as I saw for myself on a trip to the new unofficial border with South Ossetia, is a blow to Georgian pride. But the reality, says Shorena Shaverdashvili, editor of the news magazine Liberali, is that two and a half years after the war “the Russians have shot all their bullets—there isn’t very much more they can do to us.” (Georgians claim that over 400 died in that war.) The dispute about Abkhazia and South Ossetia has been frozen and internationalised. Georgian officials like to appeal to the western conscience by stressing the Russian threat, but their heart isn’t in it, and it clashes with the other story they want to tell about what a stable place their country is to do business.

As the Russians intended, the conflict blocked Nato membership for Georgia. Full EU membership is also “15 or 20 years in the future” says Tornike Gordadze, deputy minister of foreign affairs and a former Parisian academic—an assessment some would think optimistic. But so what? Georgia gets western support when it needs it, even when the west is trying to repair its relations with Russia. After the war Georgia got a £2.8bn loan from the US and Europe and, on the first anniversary of the war, Barack Obama telephoned Dmitry Medvedev to caution him about hostile Russian troop manoeuvres near the border. (The Georgian government, which named a highway after George W Bush, directs most of its disappointment with the west at Europe rather than the US, but Georgia may well conclude a free trade deal with the EU in the next few years.)

*****

After the shock of the war in 2008, and a shrinking economy and disruptive (but better-handled) opposition demonstrations in 2009, the Georgian experiment appears to be back on track. Growth in 2010 is predicted to be around 6 per cent. Meanwhile, Saakashvili and his ministers beat their chests about how many delegations they receive from surrounding countries (even discreetly from Russia) to study their success against corruption and with electoral and tax reforms and so on. And the “regional hub” strategy of economic and cultural openness, which has extended beyond free trade to visa-free travel for countries in the neighbourhood (including Iran), is in its infancy. Perhaps it won’t be long before middle-class Iranians are taking holiday breaks in the smart hotels of Batumi on the Black Sea.

Georgia is a laboratory. And it is impossible not to be impressed by some of the technicians: leading members of the often foreign-educated, English-speaking, youthful generation who seized power in 2003, having incubated their ideas in government or Tbilisi think tanks in the late 1990s. They are a different species from the older Soviet generation. Take the poised, well-dressed 32-year-old Eka Zguladze, a minister since 2007 in the crucial Interior Ministry. She describes in a matter-of-fact way the culture change in the police: “We were idealistic. My parents and grandparents didn’t think it was possible. We had to change a whole consensus, so the wife and kids of the policeman stopped seeing corruption as inevitable and came to despise it.” Or Giga Bokeria, 38, secretary of the National Security Council, a former student leader who, despite being a practising Orthodox Christian, once got beaten up for defending the religious freedom of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

This young elite had studied the texts of economic and political liberalism and, unlike us blasé westerners, still believed in the power of ideas to transform society. The Georgian experiment has also sucked in foreign fellow travellers like Raphaël Glucksmann, son of André Glucksmann, the former French Marxist who publicly abandoned the old religion in the 1980s. You can see the attraction. This is a place where you can get things done, whether it is big experiments like the flat tax or smaller things like recruiting 10,000 teachers of English from abroad (so that English rather than Russian, becomes Georgia’s second language) and giving all schoolchildren a free laptop.

But the Tbilisi elite are an intriguing mix of idealism and cynicism. They know that democratic politics is, at times, a low game and that their president is a brilliant player. And therein lies Georgia’s problem. Despite its achievements, official opinion in the west—governments, NGOs and so on—remains rather sniffy about it. Back in London, I bumped into a senior figure in Britain’s security services; when I told him where I had been he said dismissively, “so you got the full propaganda blast did you?”

Yes, I did. And yes, they do put a lot of energy into PR (see the recent adverts in the Economist and FT highlighting Georgia’s success in an index for ease of doing business). And yes, the experiment has many flaws. Two in particular. First, it is only half a western democracy; it does not yet have a proper opposition or a fully independent judiciary or media. Second, its economy is running on too much Friedman-ite idealism and suffers chronic underemployment and poverty.

On Georgia’s democratic deficit there is a wide consensus that includes the country’s divided opposition, foreign observers, and even government ministers. When I described the country to Saakashvili as “a benign one-party state” he didn’t protest but countered with how they are grafting BBC-style impartiality onto the main public television channel. He talked about the appointment of judges for life and new jury trials.

“The country is run by five people, and because of the electoral dominance of the ruling party the parliament is a rubber stamp,” says journalist Shorena Shaverdashvili. “The trouble is that all the well-educated progressive people got sucked into the government or the pro-government media and think tanks.”

The point where the three weaknesses—opposition, judiciary and media—intersect is the tax police. Opposition parties and media are weak partly because nobody with money dares to support them, knowing that if they did they could receive a visit from the tax police who would threaten them with prosecution. And in a country with a very low acquittal rate that would mean a period in jail or the payment of a large fine to the government.

Georgia is setting itself up as a model, and asking to be judged by western standards, so such criticisms are perfectly valid—even if one should remember that the country has only been fully independent for 20 years, has 20 per cent of its land occupied by Russia, and has never had a constitutional transfer of power (and in a such a small country a determined crowd of 150,000 is probably enough to do it unconstitutionally).

Levan Ramishvili, head of the Liberty Institute, the think tank that the president once worked for, has an unusual defence of the status quo: “Party-based political pluralism only exists in urbanised, educated western societies and we are not yet there. You should compare us with Latin America.” Ramishvili is the radical liberal conscience of the Rose revolution but worries more about deviations from free-market orthodoxy than political failings, in particular the populist temptation to overpromise and allow public spending to rise too fast.

But there is a more basic economic problem: the country doesn’t produce enough. Moreover inflation is over 10 per cent and the public finances are problematic. “There is a lot of free-market wishful thinking,” said one ambassador. “By unilaterally opening its economic borders Georgia has allowed Turkey to dump its agricultural produce and its building materials. Exports have not recovered from the closure of the Russian market and despite the claim that this has forced them to diversify markets and improve their wine, it’s still pretty awful. The only places that work are Tbilisi, Batumi and the port of Poti.”

*****

The “true believers” reject the idea that an economy can be too open. But they need to attract more inward investment and raise their exports sharply to prove that dictum correct. There is potential in financial services, hydropower and tourism, but it won’t create many jobs for the 30 per cent of people who don’t have proper ones. The government now promises to focus on agriculture but only 1 per cent of the budget is dedicated to it and Bakur Kvezereli, the minister, is an inexperienced 27 year old. There is a natural slot for an opposition here: slightly left of centre, pressing on social and countryside issues, and a bit less anti-Russian. There is a Christian Democratic party that occupies roughly this space, although it has no credible leader.

Until a decent opposition leader emerges Georgia will be run by Saakashvili’s kitchen cabinet, or just by Saakashvili himself. A recent constitutional shake-up is switching Georgia from a presidential to a parliamentary system in which the prime minister is the most powerful figure. The talk of political Tbilisi is whether Saakashvili will run for PM when his second and final term as president ends in 2013, mimicking the move by Vladimir Putin, Russia’s former president and now prime minister.

Will he or won’t he? I asked everyone I met and most guessed he would stand. But that would be bad news for his international reputation, and for Georgia’s struggle to embrace a less controlled form of democracy. I think Saakashvili understands this, and does not want his legacy to be that he “did a Putin.”

While I was in Tbilisi a new subsidiary of Georgian public television was launched, run by Robert Parsons, a British journalist. Called PIK, it aims to broadcast (in Russian) to neighbouring countries—Chechnya, Dagestan, Ingushetia and so on—covering what Parsons described as the northern Caucasus “intifada.” PIK is a sophisticated agent of Georgian soft power, a vast improvement on the Russian hard power that the Caucasus knows only too well. But it also reflects Georgia in all its messy reality—the highlight of the launch night was a two-hour interview with none other than Mikheil Saakashvili.

----

TALKING TO MISHA

The Georgian president tells David Goodhart why his country is a threat to Russian ambition

Outside Mikheil Saakashvili’s modern, glass-topped presidential palace, with spectacular views down over the hills of Tbilisi, there is a steel sculpture of three moving shapes representing the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. The sculptor is Gabriela von Habsburg, granddaughter of the last Emperor of Austria, and currently Georgia’s ambassador to Germany. The three shapes are of equal size. If the sculpture was true to life the executive would be several times larger than the other two. But the shapes and their creator tell you a lot about contemporary Georgia.

This is a land with an idealistic attachment to western liberal values (even if sometimes observed more in the breach) and a president capable of charming not only his own people but attracting foreigners, such as the glamorous Gabriela, to the cause. The antechamber to his office is covered in photos of Saakashvili with world leaders; there are framed cuttings too. One of them describes him as a “born showman.” He clearly relishes his rogueish image and has a western ease and openness that is strange to this part of the world.

Saakashvili—or Misha, as everyone calls him—is the son of Tbilisi intellectuals. He speaks good, accented English, thanks in part to a period at law school in New York. A large, lively man of 43, he sat behind a vast desk covered in the detritus of high office when I met him.

When I ask about his legacy—he has run the country since the pro-western revolution of 2003 and is now halfway through his second and final term as president—he says he prefers to look ahead to his remaining years in office. He reminds me that “our very survival is still not self-evident… the existential issue is still there when your largest neighbour [Russia] does not recognise your borders or your government.”

Then he launches into a list of what he wants to do next. Fully aware that the main western criticism of Georgia is that power is too concentrated on him, he waves around architects’ plans of the new parliament building being erected in Kutaisi, Georgia’s second largest city, which is being rebuilt to house Tbilisi’s political class. “The whole political psychology of the country will change,” he says. “This decentralisation is what the Rose revolution was all about, it’s not just about escaping the old Soviet elite but the centuries-old elite that has run things. We want an open, democratic system for all our nearly 5m people.”

The list continues. A reform of education. A revolution in the struggling agricultural sector, led by a few hundred South African Boers due in Georgia next year to improve farming techniques. Fast trains and better highways. “And after we’ve done all that, things might become a bit boring here,” he smiles, mocking his own over-ambition.

He returns to Russia’s presence in occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia and then, contradicting this implied vulnerability, launches into a discourse on Georgia’s soft power. “We are a clear threat to Russia’s ambition to control all central Asian energy routes to Europe, but something that is not detected by outsiders is the soft power of Georgia: we offer an alternative pole of attraction. The president of Armenia always quotes our reforms, the Ukrainian government has sent ministers to study our police reform, our tax reform, our anti-corruption measures, the president of Kyrgyzstan had a meeting recently with Obama and half of it was about how she wants to copy our reforms. After the war Russia wanted to isolate and strangle us, but it hasn’t happened.”

Indeed some rich Russians are even warming towards Georgia. He fishes around for a copy of Russian GQ magazine and holds it up to reveal a picture of a half-naked woman entwined by a snake. “Russian GQ described us like we used to imagine Reagan’s America—paradise!—that must have annoyed Putin.”

We touch on Georgia’s blocked path to Nato, despite sending troops to Iraq and Afghanistan. Saakashvili maintains it will happen one day but says: “we are the best pupil in the class but they won’t allow us to go on to the next grade.”

Negotiations with the EU over trade are more fruitful although full membership is a distant dream, with the EU’s growth now all but frozen. I ask about the conflict between the idea of Georgia as a free-market haven like Dubai and its desire to join the “official” western economy which requires adherence to all sorts of regulations from labour codes to food safety. He admits there is a tension and talks of Estonia—a liberal economy within the EU—as the model. I am told later by one of his aides that the mention of Estonia represents the victory of pragmatists over free market ideologues.

When I put the criticism to him that Georgia is a benign one-party state without a proper opposition or independent judiciary, he seems to half agree, citing the “political suicide” of the opposition two years ago. He claims that the opposition is now getting its act together and hitting the government on social issues (there is only a very basic welfare state) and could realistically get more than half of the vote. He also talks about a recent surge of confidence in the courts.

So, finally, that big question—is he going to stand “Putin-style” as prime minister in 2013 as a recent change to the constitution allows? He first goes on a detour about how happy he is that all big institutions in Georgia are now more popular than him—and contrasts this with how “uninstitutionalised” and “personal” power is in Putin’s Russia. He will not be drawn on the question itself, although he does say that he doesn’t want to be a “lame duck” president. I thought his reticence implies that he has decided not to stand. If so, it will be a relief to many of Georgia’s western well-wishers.

Could he go off to do a big international job? One Tbilisi insider laughed at the idea when I suggested it, saying that Saakashvili is too impatient to sit in committees all day. I suggest to the president that he should put himself in charge of the project of decentralising politics and perhaps come back as prime minister a few years later. “I don’t believe in comebacks,” he says and grins his big grin.

Source: prospectmagazine.co.uk

BUCH: Pasternak und die georgische Dichtung. Romantische Tradition und die Dekolonisierung der Poesie im 20.Jahrhundert. Von Mariam Parsadanishvili

Die vorliegende Arbeit widmet sich dem Thema Kaukasus und Georgien im \'Werk\' von Boris Pasternak. Der Kaukasus hat bereits eine lange Tradition in der russischen Literatur, insbesondere in der Romantik. Das Thema \'Pasternak und der Kaukasus bzw. Georgien\' umfasst in dieser Arbeit sowohl Pasternaks eigene Gedichte und Gedichtbände, in denen er diesen Raum thematisierte, als auch seine Übersetzungen georgischer Dichtung, an denen er ab 1933 bis zu seinem Lebensende arbeitete. Als Einstieg in das Thema Pasternak und Georgien behandelt das erste Kapitel Pasternaks Reisen nach Georgien und seine ersten Begegnungen mit der Literaturwelt Georgiens der 1930er Jahre. Eine zentrale und bisher unerforschte Frage dieser Arbeit ist, ob sich in diesen Übersetzungen Anlehnungen und Hinweise einerseits auf die Pasternaks eigene Werke und andererseits auf die romantische Dichtung des Kaukasus feststellen lassen. Die Frage danach, inwieweit Pasternak die Übersetzungstexte der georgischen Dichtung als eigene aneignete ist hier zentral.

Mariami Parsadanishvili, geboren in Georgien, studierte Slavistik, Geschichte und Germanistik in Telavi, Konstanz und Warschau. Derz. arbeitet und promoviert sie im Forschungsprojekt \"Georgien und Russland. Prozesse der Desintegration seit 1970\" an der Uni Konstanz und ist als freiberufliche Übersetzerin und Trainerin für Int.Kommunikation tätig

AmazonShop: Books, Maps, Videos, Music & Gifts About The Caucasus

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

PAPER: SWP-Analyse, Oestliche Partnerschaft der EU in Georgien (swp-berlin.org)

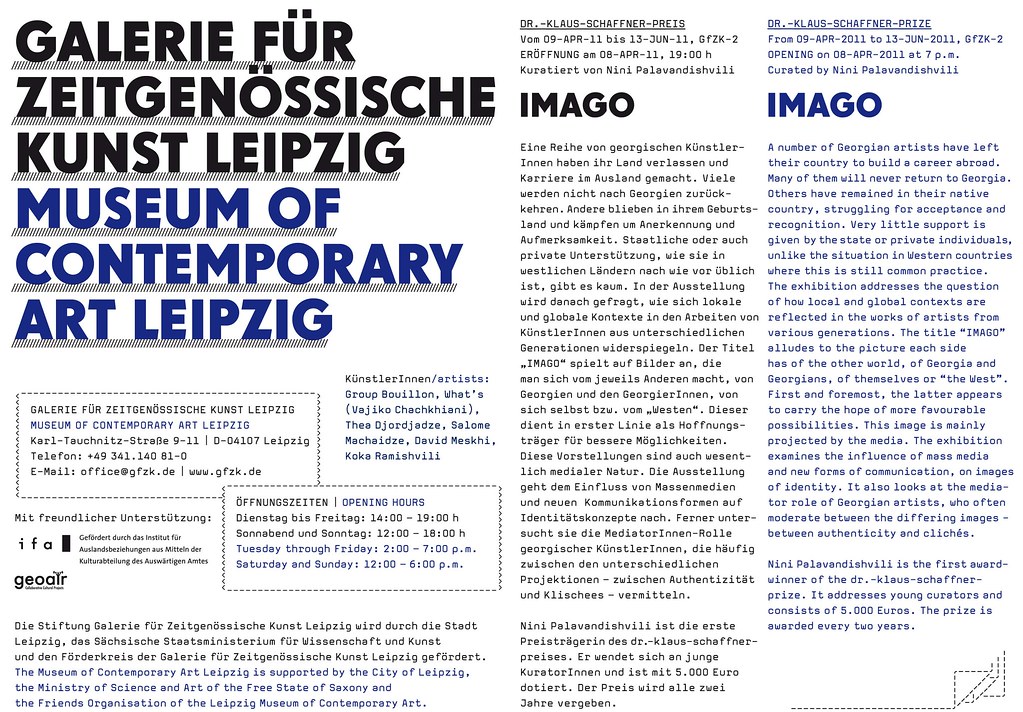

AUSSTELLUNG: IMAGO - Curated by Nini Palavandishvili (gfzk.de)

click on the flyer for a larger version!

click on the flyer for a larger version! Nini Palavandishvili ist die erste Preisträgerin des dr.-klaus-schaffnerpreises. Er wendet sich an junge KuratorInnen und ist mit 5.000 Euro dotiert. Der Preis wird alle zwei Jahre vergeben. (Congratulations!!!)

Vom 09-APR -2011 bis 13-JUN-2011, GfZK-2

Eröffnung am 08-APR -2011 um 19:00 h

Kuratiert von Nini Palavandishvili

From 09-APR -2011 to 13-JUN-2011, GfZK-2

Opening on 08-APR -2011 at 7 p.m.

Curated by Nini Palavandishvili

KünstlerInnen / Artists: Group Bouillon, What’s (Vajiko Chachkhiani), Thea Djordjadze, David Meskhi, Salome Machaidze, Koka Ramishvili

+++

Eine Reihe von georgischen KünstlerInnen haben ihr Land verlassen und Karriere im Ausland gemacht. Viele werden nicht nach Georgien zurückkehren. Andere blieben in ihrem Geburtsland und kämpfen um Anerkennung und Aufmerksamkeit. Staatliche oder auch private Unterstützung, wie sie in westlichen Ländern nach wie vor üblich ist, gibt es kaum. In der Ausstellung wird danach gefragt, wie sich lokale und globale Kontexte in den Arbeiten von KünstlerInnen aus unterschiedlichen Generationen widerspiegeln. Der Titel „IMAGO” spielt auf Bilder an, die man sich vom jeweils Anderen macht, von Georgien und den GeorgierInnen, von sich selbst bzw. vom „Westen“. Dieser dient in erster Linie als Hoffnungsträger für bessere Möglichkeiten. Diese Vorstellungen sind auch wesentlich medialer Natur. Die Ausstellung geht dem Einfluss von Massenmedien und neuen Kommunikationsformen auf Identitätskonzepte nach. Ferner untersucht sie die MediatorInnen-Rolle georgischer KünstlerInnen, die häufig zwischen den unterschiedlichen Projektionen – zwischen Authentizität und Klischees – vermitteln.

+++

A number of Georgian artists have left their country to build a career abroad. Many of them will never return to Georgia. Others have remained in their native country, struggling for acceptance and recognition. Very little support is given by the state or private individuals, unlike the situation in Western countries where this is still common practice. The exhibition addresses the question of how local and global contexts are reflected in the works of artists from various generations. The title “IMAGO” alludes to the picture each side has of the other world, of Georgia and Georgians, of ourselves or “the West”. First and foremost, the latter appears to carry the hope of more favourable possibilities. This image is mainly projected by the media. The exhibition examines the influence of mass media and new forms of communication, on images of identity. It also looks at the mediator role of Georgian artists, who often moderate between the differing images - between authenticity and clichés.

Mit freundlicher Unterstützung:

IFA (Instituts für Auslandsbeziehungen)

GeoAIR

Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig

Museum of contemporar by art leipzig

Karl-Tauchnitz-Straße 9-11

D-04107 Leipzig

Telefon: +49 341.140 81-0

E-Mail: office@gfzk.de www.gfzk.de

Sunday, March 27, 2011

PODCAST: Abchasien. Georgiens Umgang mit Flüchtlingen. Ein Beitrag von Gesine Dornblüth (wissen.dradio.de)

Es ist nicht einfach, die alte Heimat aufzugeben. Viele Vertriebene verlassen ihr Zuhause, mit der Hoffnung irgendwann zurückzukehren. Darauf haben auch die Vertriebenen aus Abchasien gehofft. Anfang der 90er Jahre wurden etwa 250.000 Georgier aus der abtrünnigen georgischen Provinz Abchasien vertrieben. Rund 30.000 Tausend Menschen flüchteten zusätzlich nach Georgien. Sie glaubten höchstens für ein paar Monate im Exil zu bleiben.

Flüchtlinge werden ausgegrenzt Inzwischen leben die Vertriebenen aus Abchasien seit fast 20 Jahren in Georgien und immer noch hausen sie in Notunterkünften. Sie warten auf Wohnungen und auf Entschädigungen. Für die Integration hat die georgische Regierung nichts getan. Sie fühlen sich immer noch ausgegrenzt und alleine gelassen. Doch die Regierung hat versprochen, sich um ihre Probleme zu kümmern und ihnen zu helfen. Mit internationalen Geldern werden Wohnungen gebaut. Gesine Dornblüt berichtet über die Situation der Vertriebenen in Georgien.

Podcast: wissen.dradio.de/podcast

Quelle: wissen.dradio.de

TALK: WiP - Social Capital in Georgia - Hans Gutbrod (crrccenters.org)

ISET Lecture Room, Zandukeli St. 16, Tbilisi, Georgia American Councils and the Caucasus Research Resource Centers (CRRC) present the 10th talk in the Spring 2011 Works-in-Progress Series:

... Dr. Hans Gutbrod, CRRC Regional Director "Social Capital in Georgia"

Social bonds between friends and family in Georgia are incredibly strong. In more institutional ways, however, social capital is poorly developed. This can be seen in every corner of Georgian society, from the failure of farmers to act collectively in buying and selling, to the crumbling stairwells in apartment blocks. Based on extensive CRRC research, the presentation will show the ways in which social capital is important and highlight how to overcome the obstacles standing in the way of further collaboration: apathy, distrust, reluctance to institutionalize, and social economic challenges. The presentation will also touch upon broader recommendations for how social capital can be developed in Georgia. Anyone wishing to receive the report with findings from the research in advance of the presentation should send an email to wip@crrccenters.org by Tuesday, March 29 (COB).

********

W-i-P is an ongoing academic discussion series based in Tbilisi, Georgia, that takes place every Wednesday at the International School of Economics (ISET) building (16 Zandukeli Street). It is co-organized by CRRC and the American Councils for International Education: ACTR/ACCELS. The purpose of the W-i-P series is to provide support and productive criticism to those researching and developing academic projects pertaining the Caucasus region. Would you like to present at one of the W-i-P sessions? Send an e-mail to wip@crrccenters.org.

RADIO: folkradio.ge from Georgia in the Caucasus (folkradio.ge)

Folk-Radio is the first and only radio station in Georgia to broadcast folk music 24 hours a day. The Georgian listeners can appreciate not only the traditional folk music of their own country, but also the music, traditions, rituals and folklore of other nations.

Folk-Radio is the first and only radio station in Georgia to broadcast folk music 24 hours a day. The Georgian listeners can appreciate not only the traditional folk music of their own country, but also the music, traditions, rituals and folklore of other nations. Friday, March 25, 2011

ELECTRONIC MUSIC: TBA: process music - Interview with Tusia Beridze (factmag.com)

“My music is as apolitical as I am…I think it would be a big undermining of the process of music-making to waste it on politics.”

Natalie Beridze is not your typical electronic music producer. Hailing from war-ravaged Georgia, her work is inventive and exploratory, yes, but always playful and highly personal – music that looks inwards for inspiration. Releasing and performing mainly under variations of the name TBA, Beridze rose to prominence in the mid-noughties through her work with the Goslab collective and then her association with Thomas Brinkmann. She has collaborated with Brinkmann on techno-oriented material as Tba Empty, and has released some of her best work on his Max.Ernst imprint, including her breakthrough record, 2005′s Annule. Combining dancefloor-primed tracks (what Beridze describes as “straight-beat”) in the microhouse mode with more delicate, contemplative compositions, Annule has deservedly earned cult status in the five years since its release, and like all Beridze’s productions, it deserves to find an even wider audience, and no doubt will in time.

Now dividing her time between Tbilisi and Berlin, Beridze looks to be entering a new purple patch in what has already been a highly fruitful career. In 2010 she’s set to follow up her Pending album for Laboratory Instinct (a platform for releases by A Guy Called Gerald, Atom TM and Daedalus, among others) with a new club-focussed 12″, ‘Straight Base Drum’, heralding a new LP for Monika Enterprise, the Berlin-based label operated by Gudrun Gut. It includes a collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto, following her contribution to his chain-music project.

As part of our continued collaboration with the Alpha-ville festival to shed light on some of the lesser-known talents in the electronic music sphere, FACT spoke to Natalie about her past, present and projected future work. You can also listen to an exclusive podcast made by TBA for Alpha-ville by clicking the link below.

Listen: Alpha-Podcast presents TBA

You studied political science prior to releasing records. Is your work as a musician political? Do you consider yourself a particularly political or confrontational artist?

“I did my masters in Political Science and later in Media only because I didn’t know what to do after I was finished with my post-graduate. Four years of wasting time…and although I realised how ridiculous it would be for me to study politics, I passed those vicious exams and even got my masters at the end of the year. Frankly I just tried to avoid starting a job, so I filled up every second of my spare time. I didn’t know I was going to make music back then…[laughs]

“My music is as apolitical as I am. I don’t think I even have a clear message or a statement to convey. Or at least I tend not to think about it in the process of making music. I think it would be a big undermining of the process of art and-music-making to waste it on politics. Process of work is probably the only area of absolute intimacy and freedom. Those two things have absolutely no resemblance to politics.”

“Process of work is probably the only area of absolute intimacy and freedom.”

What is Goslab?

“It was a group of friends, who wanted to play creative games and hang out the best they could in given circumstances…It was not long after the civil war in Georgia, which was followed by another war in Abkhazia, leaving the country crumbling. It was a time of fear and confusion – of electric black-outs, felony, isolation. A time of anguish and despair. But nevertheless there was a huge wave of commitment and eagerness to pull through. In a sense the only way to break through was to stick together and surf on a wave different to reality. We named it Goslab for better sense of integrity and togetherness, and we had fun…

“Nowadays there is no more need for collective effort, since there’s no more hindrance as such. So we all work separately. Goslab is now a recollection.”

How has changing technology influenced your artistic practice? Do you have a core set-up that never changes are you always adding to it, looking for ways to improve it?

“I’d be lying if I said I was a high-tech addict or perfectionist. I more or less have a reference of the perfect sound from the perfect speakers, since I had an experience of working with them. Nowadays I’m back to shitty ones, but the reference does it’s job [laughs]. Fruity Loops is my absolute favourite. I’d never trade it for anything. So that’s pretty much my core set-up. Plus the mic…”

“It was a time of fear and confusion – of electric black-outs, felony, isolation.”

Tell us about the podcast you recorded for Alpha-ville – what aspects of your work does it represent?

“The mix I made is of music which I not only admire, but which is also literally part of my life. The idea was to mix music has inspired me lately, so I just skipped through my iPod for honesty of choice [laughs], and I took the playlist which has been there forever. I doubt that this selection would ever become boring for me.”

Were there any particular artists or works that really inspired you to embark on your own career as an artist?

“Me becoming an artist was a result of coincidence and sheer luck. I did know that I would be an artist, but I didn’t have any preference for, or commitment to, one particular discipline. My friends were doing electronic music back then and I found it stunning that you could produce music without even basic knowledge of notation et cetera, so I got myself an ugly desktop computer and installed Fruity Loops. I was lucky, firstly because I had people around me who were motivating and gave me a sense of determination to do music. And I was lucky because I got a record deal in less then a year.

“Additionally, I undoubtedly was, and always will be, inspired by the legacy of truly outstanding composers and artists, the list of which is a bit too long to recall in full. I’ll avoid relaying the names, so as not to leave anyone out.”

“I wanted to be with the man who would become my husband, in Cologne, and instead I was trapped in Tiflis, Georgia.”

The first album I ever heard by you was Annule (Max.Ernst, 2005). Can you tell us about that origins of that record? How do you feel about it now?

“It was the third album I did, and strangely it sold the best. The title track ‘Annule’ was recorded in a desperate need of a Schengen Visa, which I was rejected in most of the consulates of Georgia. I wanted to be with the man who would become my husband, in Cologne, and instead I was trapped in Tiflis, Georgia. That’s the story of the cover artwork and the title track. This album was the first time I tried straight beat and rap [laughs]. I also found out that merging different styles of music is probably the most interesting way for me to put together an album. That’s how I’ve done it ever since…”

What other up-and-coming artists are you into at the moment? Any recommendations of people we should check out?

“Nika Machaidze AKA Nikakoi.”

You make a lot of broken, rhythmically abstract music, but you’ve also made tracks that are more club-oriented, rooted in house/techno. Do you think of any of your music as “dance” music? Does dance music interest you?

Tba Empty’s Stupid Rotation is the first dance album I made. It’s something I always loved and wanted to do, but never thought I could. Techno was always one of the biggest inspiration sources to me. It has the most qualitative and functional emptiness in it. There’s no other construction that has so much room for thought inside.

“In the beginning I thought that I’d never be able to produce anything groovy enough to make me dance. With Stupid Rotation I was startled to find out that I can make a club full of people dance for hours and that playing live can actually be so much fun. Since that album I put out several EP and LP s with a pure, straight beat. For me, it’s much more difficult to produce a good techno track then a good song or a composition for piano. And it is 100% due to Thomas Brinkmann that I sometimes make straight-beat.”

“Techno was always one of the biggest inspiration sources to me…There’s no other construction that has so much room for thought inside.”

What reaction are you trying to provoke with your music? What message, if any, are you trying to convey?

“I’m truly happy if my music is able to reach the listener. I never think of putting any concrete message into music. It’s as abstract and metaphysical as poetry. Initially you make music or art because you feel the urge to say something, but I don’t care about the content of what I’m saying.

“It doesn’t matter if what you say is accurate and true. I don’t care about facts, because myths are much more alive, bewitching and creative, because they provoke development and process. Most importantly they have ability to live and inspire further on, beyond the feasible verge. So if my music succeeds in reaching someone and changing just a tiny little detail, or making one’s day – then i think I’ve done a good job [laughs].”

Where do you live and work? In the city? How have your surroundings affected the kind of work you make?

“In Tbilisi and in Berlin. I really don’t know if my surroundings have much to do with my work. It’s always hard for me to answer this question, because once again my understanding of music and the process of making music is way too focussed on individual approach. That certainly involves the environment and surroundings in which an artist was raised and formed. But at the end of the day music is more wide-ranging and extensive then cultural bounds, it is an integrated part of our inner world. That’s the place it interacts with, and derives from.”

“I became lazy because I make music, which is a pure luxury – it requires nothing but a moment of peace and contemplation.”

You’ve made several films, right? Are you still working with visual media? Is the visual aspect of your performances important to you?

“I’ve made actually just one video and luckily enough it won a prize at the film festival. I guess that’s why people think that i make video art too…

“Right now I don’t do any visual media at all. It’s too focused for me. Somehow I think that besides the form, it also requires a great deal of ideas. And me – I totally lack ideas. I became lazy because I make music, which is a pure luxury – it requires nothing but a moment of peace and contemplation.”

You released several records on Max Ernst. Did the music and ideas of Brinkmann and the label influence you in any way?

“Absolutely. Thomas taught me probably the most important thing: to be able to confront your limits and go beyond them. His music is just as uncompromising and unconditional as his character. Max.Ernst [Brinkmann's label] gave me and my music a chance to find it’s way in the world. And the way this label works is probably the most incorruptible and self-aware that I have ever encountered.”

“The way Thomas Brinkmann and Max.Ernst works is probably the most incorruptible and self-aware that I have ever encountered.”

How do you feel the climate, audience and market for electronic music such as your own changed in the years since you began your career as an artist?

“I think it was already too late and too burdensome to become big with the small labels when I began making music. It was already not ‘the right place and the right time’ kind of thing, because by that point electronic music had its front-runners and the canon had been formed. Nowadays the scene is even more hostile for the newcomers, because music doesn’t sell, unless it’s from the ‘big name’ and unless millions of dollars were invested in it beforehand. The MP3 download era is not exactly very friendly with the labels, distributors and artists. We all have to think twice before spending money on a moderate 2,000 copies. But even that is not a good enough hindrance for artists. And even though there’s just too much music and too many labels nowadays, I still encounter outstanding and quality music sometimes, and that’s just about enough.”

Tell us about your work on chain-music…

“One day I got a mail from Ryuichi Sakamoto, who wanted me to participate in the project. I sent him lot of music and we chose one track. Later on we collaborated on one track, which is going to be part of the album I’m releasing on Monika, in september.

What else do you have lined up for 2010?

“An online EP release on Monika (actually happening right now), also a CD release in September, on Monika, and vinyl (‘Straight Base Drum’) on Laboratory Instinct. “I’m also working on a feature animation film soundtrack…very excited about this.”

Kiran Sande

Wednesday, March 23, 2011

AUSSTELLUNG: "Die Seele Georgiens“. Fotografie von Wolfgang Korall +++ in Berlin (embassy.mfa.gov.ge)

Gabriela von Habsburg

Gabriela von HabsburgBotschafterin von Georgien,

geben sich die Ehre

zur Eröffnung der Fotoausstellung von

Wolfgang Korall

"Die Seele Georgiens"

am Dienstag, den 29. März 2011 um 18.00 Uhr

Rauchstraße 11, 10787 Berlin

Im Anschluss Empfang mit georgischem Wein und georgischen Spezialitäten.

Botschaft von Georgien

Rauchstr.11

10787 Berlin

Tel. 030 484907-13

Fax. 030 484907-20

www.germany.mfa.gov.ge

Monday, March 21, 2011

TELEVISION/VIDEO: Schön, schrill, geistreich – Künstler in Tbilisi. Von Katrin Molnár und Ralph Hälbig (mdr.de)

Ein Film von Katrin Molnár und Ralph Hälbig

Lebendige Folklore und Tradition – der georgische Alltag ist voll davon. Doch in den Hinterhöfen von Tbilisi existiert auch eine andere Welt – eine Welt, die sich moderner Kunst und zeitgenössischem Design verschrieben hat.

Ob Fotografie, Streetart, Performance-Kunst oder Raumgestaltung – überall dürstet man nach neuen Formen und klugen Inhalten: Lederkleider, die zu Skulpturen der Erbsünde werden, Fotos, die die Frau als "schönste Seele der Natur" zeigen, und Graffiti, die Sexualität enttabuisieren.

Obwohl einige der Künstler im Ausland gefeiert werden, ringen sie im eigenen Land oft um Akzeptanz. Nur die wenigsten können von ihrer Kunst leben. Doch das hält sie nicht ab von immer quirligeren Ideen.

Mit: Irma Sharikadze, Nika Machaidze (Nikakoi), Tusia Beridze (TBA), Nino Chubinishvili (Chubiko), Keti Toloraia (ROOMS), Tamuna Gvaberidze (ROOMS), Ekaterina Lemonjava (Rock Club Tbilisi), Shadows Eye (Band aus Tbilisi), Bouillon Group, Musia Keburia.

Quelle: mdr.de

photo: Irma Sharikadze

Saturday, March 19, 2011

FILMFESTIVAL: GORELOVKA / GORELOVKA. Von ALEXANDER KVIRIA (filmfestival-goeast.de)

Wiesbaden,

Caligari, 07.04.2011, 16:00

Bellevue-Saal, 08.04.2011, 20:00

Die weite, karge Landschaft Südgeorgiens; ein Dorf, in dem die Zeit stehen geblieben scheint. Hier, in Gorelovka und Umgebung, leben die letzten Duchoborzen, wörtlich „Geisteskämpfer“, Angehörige einer christlichen, von der russisch-orthodoxen Kirche abweichenden Religionsgemeinschaft, die 1841 von Zar Nikolaus 1. aus Russland verbannt wurde. In Georgien fanden sie eine neue Heimat und lebten lange Zeit unbehelligt ihr einfaches, bäuerliches Leben, pflegten ihre Traditionen, abgeschieden vom Rest der Welt. Ihre Identität und ihren Glauben, in dem Gewaltlosigkeit und Vegetarismus fest verwurzelt sind, haben sie so bis heute bewahrt. Doch ihre Gemeinschaft löst sich langsam auf: Immer mehr, vor allem junge Leute ziehen fort und versuchen anderswo Arbeit und ein besseres Leben zu finden. Alexander Kviria porträtiert in Bildern voller Weite und Schönheit eine Welt, die nicht mehr lange existieren wird. Er zeigt, wie das Leben der Menschen bis heute durch ihre Spiritualität geprägt wird, in der Gottes Gegenwart allgegenwärtig, in jedem Lebewesen unmittelbar offenbart ist. Daher haben die Duchoborzen weder Priester noch Kirchen und keine heiligen Schriften. Psalmen und Hymnen werden von Generation zu Generation mündlich überliefert – und mit den letzten Bewohnern von Gorelovka verschwinden.

+++

Geboren 1972 in Tiflis, Georgien. Schloss 2003 ein Studium der Filmregie am Gerassimow-Institut für Kinematographie (VGIK) ab. 1999 entstand sein Filmdebüt, der dokumentarische Kurzfilm ROTTERDAM / TBILISI – NO COMMENT. Seitdem drehte er zahlreiche dokumentarische und fiktionale Kurzfilme. Kviria arbeitete für mehrere Fernsehunternehmen in Moskau und Tiflis als Journalist und Regisseur. Er lebt seit 2007 als unabhängiger Filmemacher in London.

FILMOGRAFIE (AUSWAHL)

1999 / ROTTERDAM / TBILISI – NO COMMENT (documentary)

2001 / ODNOKLASNIKI / SCHOOLMATES (documentary)

2005 / ISTORIYA MALENKOGO SOLDATA / THE STORY OF A LITTLE SOLDIER (short) 2008 / STEVEN (short)

2010 / GORELOVKA GORELOVKA

Quelle: www.filmfestival-goeast.de